Saturday, August 29, 2020

The Cars that Ate Paris (Peter Weir, 1974)

Saturday, August 15, 2020

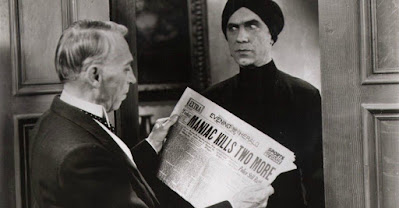

Night of Terror (Ben Stoloff, 1933)

The evening's double murder has taken place uncomfortably close to the Rinehart estate. Patriarch Richard (Tully Marshall) is an esteemed scientist and scholar, and he is sharing the estate with his science professor nephew (?)/future son-in-law (?) Arthur Hornsby (George Meeker), his daughter (?)/ward (?)/woman engaged to his nephew (?) Mary (Sally Blane), his gypsy servants Degar (Bela Lugosi) and Sika (Mary Frey), and his chauffeur Martin (Oscar Smith), a black character given much racist treatment. About Arthur and Mary. Based on the dialogue, they are possibly: (1) blood-related cousins who are going to marry each other; (2) the nephew of Richard marrying a ward of the state who has been given shelter by Richard; (3) Richard's mentee who considers Richard an avuncular figure but is not related to him marrying Richard's daughter (or ward raised as his daughter); or (4) who the hell knows? Whatever the case, Arthur seems much more interested in his experiments than in the company of his fiancee, and Mary and Tom Hartley (Wallace Ford), a fast-talking newspaper reporter covering the killings, have a strong mutual attraction, though Mary unconvincingly pretends otherwise.

The evening's double murder has taken place uncomfortably close to the Rinehart estate. Patriarch Richard (Tully Marshall) is an esteemed scientist and scholar, and he is sharing the estate with his science professor nephew (?)/future son-in-law (?) Arthur Hornsby (George Meeker), his daughter (?)/ward (?)/woman engaged to his nephew (?) Mary (Sally Blane), his gypsy servants Degar (Bela Lugosi) and Sika (Mary Frey), and his chauffeur Martin (Oscar Smith), a black character given much racist treatment. About Arthur and Mary. Based on the dialogue, they are possibly: (1) blood-related cousins who are going to marry each other; (2) the nephew of Richard marrying a ward of the state who has been given shelter by Richard; (3) Richard's mentee who considers Richard an avuncular figure but is not related to him marrying Richard's daughter (or ward raised as his daughter); or (4) who the hell knows? Whatever the case, Arthur seems much more interested in his experiments than in the company of his fiancee, and Mary and Tom Hartley (Wallace Ford), a fast-talking newspaper reporter covering the killings, have a strong mutual attraction, though Mary unconvincingly pretends otherwise.Arthur has chosen this night to test his fantastic new serum, which will allow human beings to survive without oxygen. Arthur will be buried alive and revived the following morning, with a team of scientists and science professors verifying his experiment. Meanwhile, Sika, a clairvoyant, predicts much death and sorrow heading the household's way. Into this roiling, complicated stew of interpersonal drama drops the maniac. As characters are picked off one by one, the scientists, the gypsies, Tom Hartley, the police, and Richard's brother and sister-in-law get dragged into the action. The usual '30s business ensues, followed by a twist ending, followed by one of the actors in character warning audiences not to reveal the twist to anyone who hasn't seen the movie yet.

In a decade loaded with classic horror, Night of Terror is not even an also-ran. At least it's not boring, though top-billed Lugosi isn't given much to do outside of a few fleetingly great moments. One thing I really enjoyed, though, was a verbal tic by both Richard and the chief of police. When either man was annoyed by something another character said to them, they responded with an irritated "ehhhhhhhh." I'm going to work that into my repertoire. I'm not familiar with the rest of director Stoloff's filmography, but many of their titles seem like titles TV writers would come up with if they needed some fake '20s'-'40s movie names. For example: Play Ball with Babe Ruth, Stolen Sweeties, Say It with Flour, Papa's Darling, Plastered in Paris, Speakeasy, New Movietone Follies of 1930, Soup to Nuts, Palooka, Swellhead, Three Sons o' Guns, and It's a Joke, Son!